A Linear Algebra Approach to Least Squares

In science and engineering, we rarely get perfect data. When we collect measurements \((t_i, y_i)\), they almost never fall perfectly on a straight line due to noise or experimental error. We are usually looking for the “best fit” line \(y = ct + d\) to describe the trend. But what does “best fit” or “least squares” actually mean mathematically?

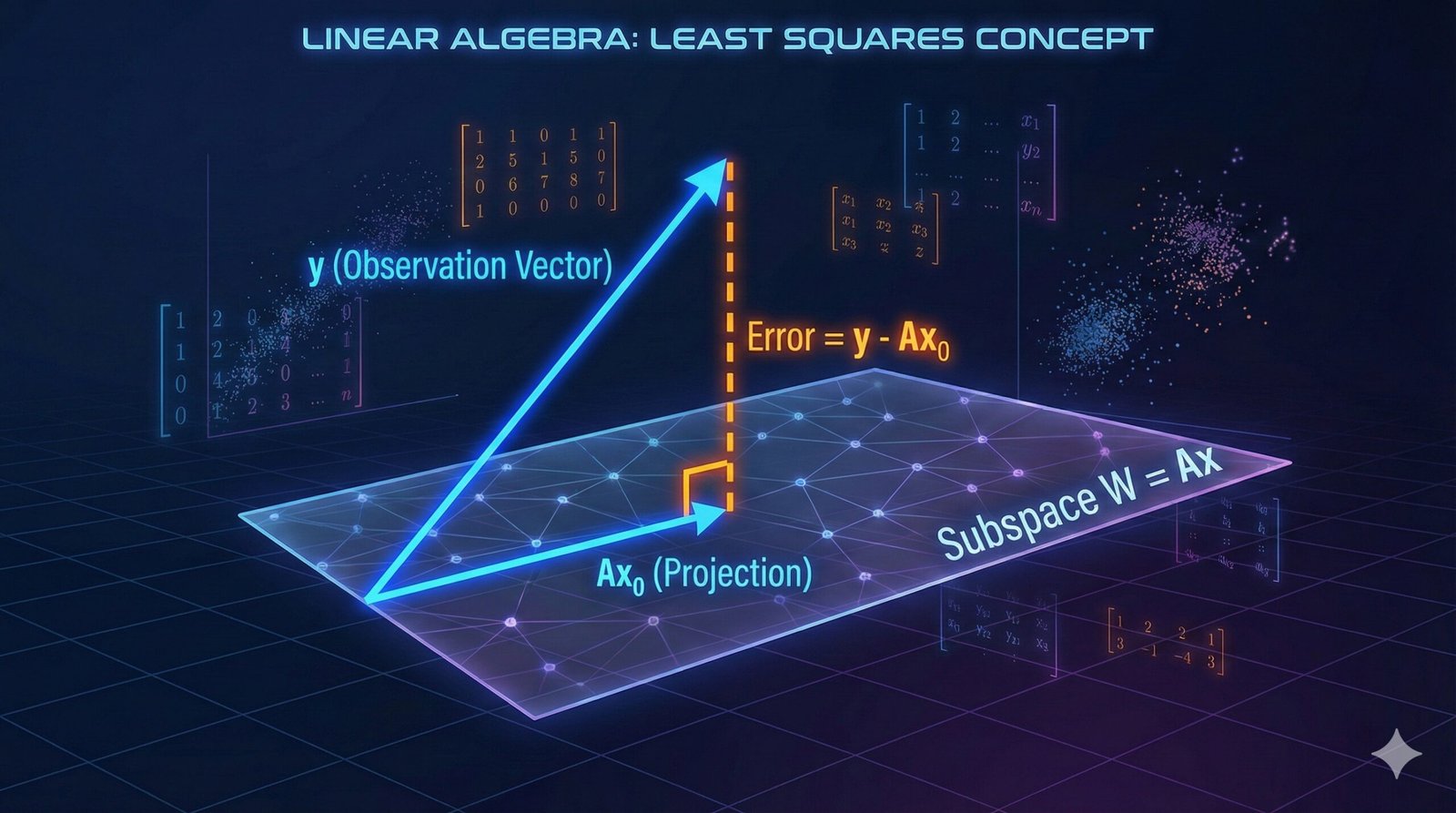

While this is often taught as a calculus problem (minimizing the sum of squared errors), it is actually a beautiful problem in Linear Algebra. It is a story about geometry, projections, and subspaces.

1. From Statistics to Linear Algebra

Let’s say we have \(m\) data points. We are trying to solve a system of linear equations that looks like this:

$$

\begin{cases} ct_1 + d = y_1 \\ ct_2 + d = y_2 \\ \vdots \\ ct_m + d = y_m \end{cases}

$$

In matrix notation, we define our Design Matrix \(A\), our Unknowns \(x\), and our Observations \(y\):

$$

A = \begin{pmatrix} t_1 & 1 \\ \vdots & \vdots \\ t_m & 1 \end{pmatrix}, \quad x = \begin{pmatrix} c \\ d \end{pmatrix}, \quad y = \begin{pmatrix} y_1 \\ \vdots \\ y_m \end{pmatrix}

$$

We want to solve \(Ax = y\). However, because of the noise, \(y\) is not in the column space of \(A\) (denoted as \(\mathsf{W}\)).

Instead of a perfect solution, we seek a vector \(x\) that minimizes the “error” \(E\). In Linear Algebra, this error is the square of the norm of the residual vector:

$$

E = || y – Ax ||^2

$$

Why \(E = || y – Ax ||^2\)?

To understand this notation, we have to look at the error for each individual data point.

1. The Individual Error

For a single data point \((t_i, y_i)\), our line predicts the value \(ct_i + d\). The difference between the actual observed value (\(y_i\)) and the predicted value is the error for that specific point:

$$

e_i = y_i – (ct_i + d)

$$

2. The Error Vector

In matrix notation, \(Ax\) represents the vector of all our predicted values:

$$

Ax = \begin{pmatrix} ct_1 + d \\ \vdots \\ ct_m + d \end{pmatrix} = \text{Predicted Values}

$$

If we subtract this prediction vector from our observation vector \(y\), we get a single vector \(e\) containing all the individual errors:

$$

e = y – Ax = \begin{pmatrix} y_1 – (ct_1 + d) \\ \vdots \\ y_m – (ct_m + d) \end{pmatrix} = \begin{pmatrix} e_1 \\ \vdots \\ e_m \end{pmatrix}

$$

3. The Squared Norm

In statistics, we want to minimize the Sum of Squared Errors (SSE) to avoid negative errors canceling out positive ones. Mathematically, this is:

$$

\text{SSE} = \sum_{i=1}^{m} e_i^2 = e_1^2 + e_2^2 + \dots + e_m^2

$$

In Linear Algebra, the length (or magnitude) of a vector \(v\) is called its Norm, denoted as \(||v||\). If we use the standard inner product here, the formula for the norm is the square root of the sum of squared components:

$$

||e|| = ||y-Ax|| = \sqrt{e_1^2 + e_2^2 + \dots + e_m^2}

$$

If we square both sides to get rid of the square root, we get exactly the Sum of Squared Errors:

$$

||e||^2 = ||y-Ax||^2 = e_1^2 + e_2^2 + \dots + e_m^2 = \text{SSE}

$$

Therefore, minimizing the sum of squared errors is mathematically identical to minimizing the squared length of the error vector:

$$

E = || \underbrace{y – Ax}_{\text{error vector}} ||^2

$$

Because the norm is always non-negative (\(||v|| \ge 0\)), finding an \(x\) that minimizes \(||y-Ax||^2\) is equivalent to finding an \(x\) that minimizes \(||y-Ax||\). Thus, the problem translates simply to: Find \(x\) such that the vector \(Ax\) is as close as possible to \(y\).

2. The Solution: Geometry of Projections

To solve this, we rely on subspaces.

Theorem 6.6: Orthogonal Decomposition

This theorem tells us that any vector \(y\) can be split uniquely into two perpendicular components relative to a subspace \(\mathsf{W}\).

Let \(\mathsf{W}\) be a finite-dimensional subspace of an inner product space \(\mathsf{V}\), and let \(y \in \mathsf{V}\). Then there exist unique vectors \(u \in \mathsf{W}\) and \(z \in \mathsf{W}^{\perp}\) such that \(y = u + z\).

Connecting to Our Least Squares Problem:

To see why this theorem is the key, we map its notation to our problem:

- The Subspace (\(\mathsf{W}\)): This matches the Column Space (Range) of our matrix \(A\), defined as \(\{Ax : x \in \mathsf{F}^n\}\).

- The Vector (\(u\)): This matches our ideal approximation \(Ax_0\). It is the “shadow” or projection of \(y\) onto the subspace \(\mathsf{W}\).

- The Vector (\(z\)): This matches our error vector \(y – Ax_0\). This represents the “noise” that is orthogonal to our model.

Corollary: The Closest Vector

The corollary to Theorem 6.6 gives us our optimization criterion.

The vector \(u\) is the unique vector in \(\mathsf{W}\) that is “closest” to \(y\); that is, \(||y – x|| \geq ||y – u||\) for all \(x \in \mathsf{W}\).

In our context, this confirms that if we can find the \(x_0\) that makes the error vector (\(y – Ax_0\)) orthogonal to the column space, we have mathematically guaranteed the minimum error.

3. The Algebraic Tools

To find the actual values for \(x\), we need two algebraic lemmas to manipulate our equations.

Lemma 1: The Adjoint Property

This allows us to move the matrix \(A\) from one side of an inner product to the other.

\(\langle Ax, y \rangle_m = \langle x, A^*y \rangle_n\)

Lemma 2: Rank Preservation

This ensures that our solution will be unique.

If \(\text{rank}(A) = n\), then \(\text{rank}(A^A) = n\). Consequently, \(A^A\) is invertible.

If \(\text{rank}(A) = n\), then \(\text{rank}(A^*A) = n\). Consequently, \(A^*A\) is invertible.

4. The Solution: Deriving the Normal Equations

We now combine the geometry (Theorem 6.6) with the algebra (Lemma 1) to solve for \(x_0\).

Step 1: The Orthogonality Condition

From Theorem 6.6, we established that the optimal error vector (\(Ax_0 – y\)) must be in \(\mathsf{W}^\perp\). This means it must be orthogonal to every vector in the column space \(\mathsf{W}\).

Since every vector in \(\mathsf{W}\) can be written as \(Ax\) for some \(x\), we can write this condition as an inner product:

$$

\langle Ax, Ax_0 – y \rangle_m = 0 \quad \text{for all } x \in \mathsf{F}^n

$$

Step 2: Moving the Matrix (Lemma 1)

We want to isolate \(x\), so we use Lemma 1 to move \(A\) from the left side of the inner product to the right side (where it becomes the adjoint \(A^*\)):

$$

\langle x, A^*(Ax_0 – y) \rangle_n = 0 \quad \text{for all } x \in \mathsf{F}^n

$$

Step 3: Solving for Zero

If the inner product of a vector \(v\) with any vector \(x\) is always 0, then \(v\) itself must be the zero vector. Therefore:

$$

A^*(Ax_0 – y) = 0

$$

Expanding this gives us:

$$

A^Ax_0 – A^y = 0 \Rightarrow A^Ax_0 = A^y

$$

Step 4: Invertibility (Lemma 2)

Finally, if we assume our data columns are linearly independent (rank(\(A\)) = \(n\)), Lemma 2 tells us that \(A^*A\) is invertible. We can multiply by the inverse to isolate \(x_0\).

This leads to Theorem 6.12:

Let \(A\) be an \(m \times n\) matrix with rank \(n\). The unique vector \(x_0\) that minimizes \(||Ax – y||\) is given by:

$$

x_0 = (A^A)^{-1}A^y

$$

These are the famous Normal Equations.

5. A Numerical Deep Dive

Let’s apply this theorem to a concrete data set to verify the geometry explicitly.

The Data:

$$

\begin{array}{c|c} t \text{ (Independent)} & y \text{ (Dependent)} \\ \hline 1 & 1.04 \\ 2 & 3.54 \\ 3 & 4.31 \\ 4 & 7.81 \\ 5 & 9.29 \\ 6 & 11.94 \\ \end{array}

$$

Step 1: Construct the Matrices

$$

A = \begin{pmatrix} 1 & 1 \\ 2 & 1 \\ 3 & 1 \\ 4 & 1 \\ 5 & 1 \\ 6 & 1 \end{pmatrix}, \quad y = \begin{pmatrix} 1.04 \\ 3.54 \\ 4.31 \\ 7.81 \\ 9.29 \\ 11.94 \end{pmatrix}

$$

Step 2: Solve for \(x\) (The Coefficients)

Using the formula \(x = (A^T A)^{-1} A^T y\), we calculate:

$$

\beta_1 \approx 2.164, \quad \beta_0 \approx -1.250

$$

So our best fit line is \(y = 2.164t – 1.250\).

6. Verifying the Geometry (Theorem 6.6)

Here is where it gets interesting. We claimed that the data \(y\) splits into a signal \(u\) and noise \(z\). Let’s calculate them.

The Signal Vector \(u\) (in \(\mathsf{W}\))

$$

u = Ax \approx \begin{pmatrix} 0.91 \\ 3.08 \\ 5.24 \\ 7.41 \\ 9.57 \\ 11.74 \end{pmatrix}

$$

- Dimension: \(\mathsf{W}\) is 2-dimensional.

- Basis of \(u\): The vector \(u\) is formed by a linear combination of the two columns of A.

The Noise Vector \(z\) (in \(\mathsf{W}^{\perp}\))

$$

z = y – u \approx \begin{pmatrix} 0.13 \\ 0.46 \\ -0.93 \\ 0.40 \\ -0.28 \\ 0.20 \end{pmatrix}

$$

Does \(z\) really live in \(\mathsf{W}^{\perp}\)?

For \(z\) to be in \(\mathsf{W}^{\perp}\), it must be orthogonal to the columns of \(A\).

$$

z \cdot \text{Column}_1(A) \approx 0

$$

$$

z \cdot \text{Column}_2(A) \approx 0

$$

Numerical checks confirm these are effectively zero (\(< 10^{-14}\)). Theorem 6.6 holds!

The Dimensionality of Error

It is worth noting the dimensions here.

- Our total space \(\mathsf{V}\) is 6-dimensional (6 data points).

- Our model space \(\mathsf{W}\) is 2-dimensional (slope and intercept).

- Therefore, our error space \(\mathsf{W}^{\perp}\) is 4-dimensional (\(6-2=4\)).

The vector \(z\) is not random; it lives in a specific 4-dimensional subspace defined by the null space of \(A^T\). We can even find a basis for this error space (4 vectors orthogonal to \(A\)) and express \(z\) as a unique combination of those basis vectors.

Conclusion

Least Squares is not just a formula to memorize. It is a projection. We project our messy, high-dimensional data \(y\) onto the clean, lower-dimensional subspace \(\mathsf{W}\) to find the shadow \(u\) that best represents reality.

References

The theorem numbering in this post follows Linear Algebra (4th Edition) by Friedberg, Insel, and Spence. Some explanations and details here differ from the book.